Paige Johnson is the author of the Playscapes blog, which at 80,000 page views per month is the most widely read source of playground design on the web.

Playgrounds can be one of the worst offenders in the struggle to make public spaces locally relevant. Following a standard recipe of ‘kit, fence and carpet’ ensures that a play space could be in Milton Keynes or Madagascar, Swindon or South LA. Without context, who’s to tell?

Adding local context to a playground installation increases community commitment to the space, involves local providers, and is just plain more fun. Localised elements can form the basis for new playground installations, or be added to improve existing ones. Here, examples from my four years of writing about playgrounds at Playscapes illustrate strategies for localising the playground.

1. Consider topography

Whenever possible, playgrounds should make the ground plane itself part of the play, preserving or reflecting local topographies.

Retaining an existing pile of rubble at a reclaimed industrial site in France allowed this playground by Agence TER to fit into a familiar local site AND be more exciting by hanging off its steep side.

Topographies can be simpler constructions as well: this spiral mound in London, made of turf by Mortar and Pestle Studio, recalls similar Elizabethan garden features.

The steep facets of a Parisian playground by BASE were inspired by the topography in a photo of a local ‘found’ playscape.

2. Use local materials creatively

Everyone has heard about the use of stones and stumps to make a ‘natural playground’. But it takes some additional thoughtfulness to turn ‘natural’ into ‘local’. Robert Tully of Colorado used wood and stone to make a play sculpture modelled on Native American trade beads, and added subtle carving on a sandpit’s cluster of boulders to suggest local turtle species.

Australian artist Fiona Foley used native seed pods for a playground in Sydney; not literally but as inspiration for the forms of playground features for the under-7 set.

Vintage playgrounds in Singapore once utilised small mosaic tiles as a unique surface treatment. New Singapore playgrounds should look for modern ways to continue this local tradition.

3. Look around for history

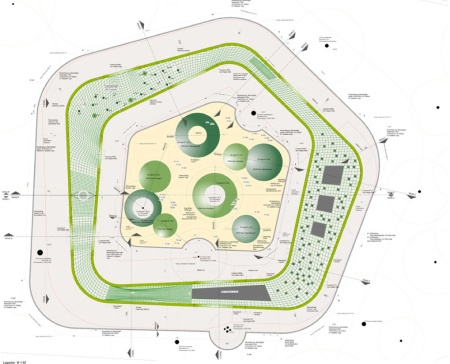

The pentagonal shape of the continuous playground climber by Annabau reflects the shape of the medieval city of Wiesbaden. Its pole and net construction dips and swoops strategically to provide sightlines to city monuments so that the playscape joins the cityscape.

At the Tower Playground, Danish playground makers Monstrum took the incorporation of local monuments one step further by making a playground entirely composed of roofs from the city of Copenhagen; fulfilling any child’s fantasy of rooftop explorations.

Sometimes looking around for history means retaining beloved features within a new scheme. Spanish firm Urbanarbolismo inexpensively rehabbed an existing playground by painting all of the features from swings to streetlamps in eye-popping orange, coordinated with new safety surfacing.

And then they planted the site by engaging the local community in a ‘Green Battle’ in which 200 people threw seed-containing mud balls at each other until the battlefield/site (and themselves) were completely covered. The seeds included a grass to green the space quickly and native species such as thyme and heather to add permanent color and aroma to the playscape.

It doesn’t get more local than residents throwing mud on each other to make a great new playground!

No public space should be so generic that it can be duplicated half a world away. Combining topography, local materials, and a sense of history help make any playground a unique site for community pride; deeply attached to its local context and sure of its place.

Tags: Landscape consultants, Resources, Sport and play, urban design, urban planning

17/08/2012 at 07:58 |

great article…..